This is a network committed to advancing clinical understanding through real-world outcomes. We believe veterinarians hold unparalleled insight into what truly works in practice. Each week, we pose one focused clinical question to the veterinary community. On Mondays, we present the question. On Fridays, we share your responses—highlighting the treatments and protocols delivering the best outcomes. Together, we’re building a living library of frontline veterinary wisdom.

Announcing: CareVet Clinical Outcomes Showcase

ALL Veterinary professionals at every level (no licensure required) are encouraged to submit solutions, ideas, innovations, or practices that are meaningfully advancing clinical outcomes – for a chance to earn $5,000.

This Week’s Outcomes: Idiopathic Epilepsy

When managing idiopathic epilepsy in dogs, what is your most common starting treatment recommendation?

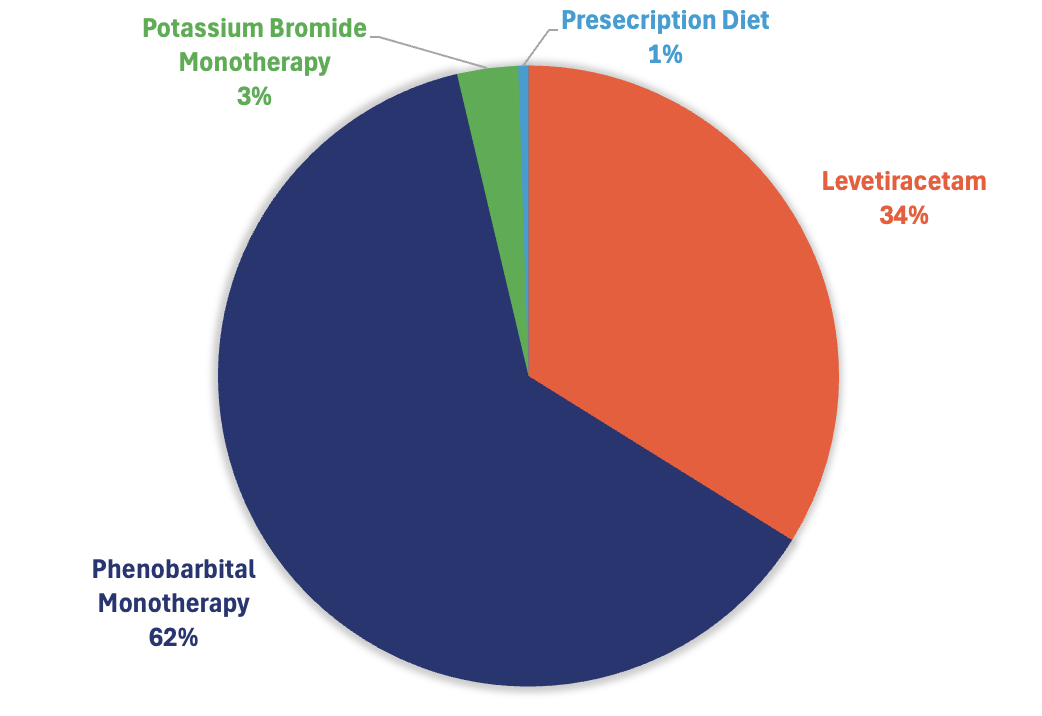

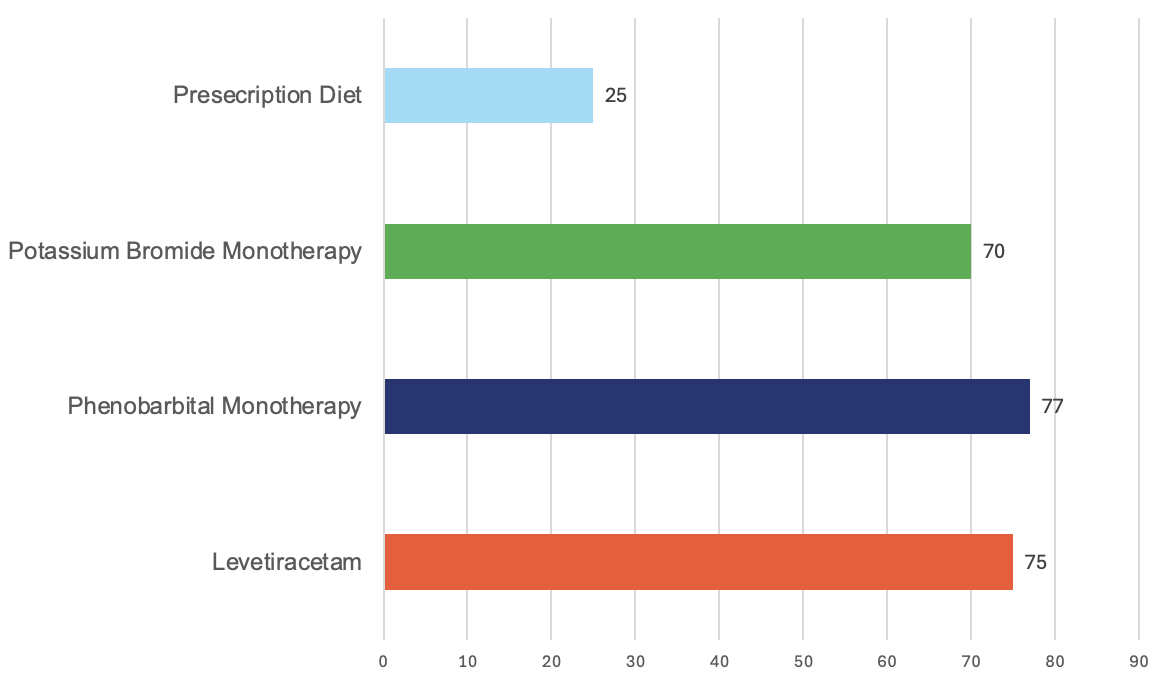

This week’s results indicate that responding DVMs often select Phenobarbital Monotherapy as their treatment of choice for idiopathic epilepsy, which is consistent with what specialist suggest.

* The pie chart illustrates the percentage of treatments selected by responding DVMs, while the bar chart displays the reported effectiveness of each treatment.

Specialist Perspective: First-Line Therapy for Idiopathic Epilepsy in Dogs

When managing idiopathic epilepsy (IE) in dogs, the question of initial therapy is not simply about seizure suppression—it is about long-term control, quality of life, safety profile, monitoring feasibility, and client compliance.

Among the options listed, the most common and evidence-supported starting recommendation remains:

Phenobarbital Monotherapy

Not because it is the newest option.

Not because it is the simplest.

But because, in aggregate clinical evidence and decades of specialty practice, it remains the most predictable, durable first-line antiseizure medication for canine idiopathic epilepsy.

Why Phenobarbital Remains First-Line

Across ACVIM consensus guidelines and multiple retrospective and prospective studies, phenobarbital consistently demonstrates:

- Reliable reduction in seizure frequency

- Established therapeutic serum range

- Clear monitoring protocols

- Long-term outcome data spanning decades

Seizure control rates with phenobarbital monotherapy are typically reported in the 60–80% range for meaningful reduction, with a substantial proportion achieving satisfactory control when appropriately dosed and monitored.

Importantly, phenobarbital’s pharmacokinetics and therapeutic window are well characterized. Serum monitoring allows objective dose optimization—an advantage not all antiseizure drugs offer with the same clarity.

From a systems perspective, phenobarbital offers:

- Cost accessibility

- Predictable titration

- Wide clinician familiarity

- Evidence-supported first-line endorsement in consensus statements

For most otherwise healthy dogs with newly diagnosed idiopathic epilepsy, phenobarbital remains the most defensible and pragmatic starting choice.

Where the Other Options Fit

Potassium Bromide Monotherapy

Potassium bromide can be effective, particularly in dogs with contraindications to phenobarbital (e.g., pre-existing hepatic compromise). However:

- It has a long half-life (weeks), delaying steady-state achievement.

- Gastrointestinal adverse effects are common.

- Bromide toxicosis risk exists with dietary variability.

- It is generally considered alternative first-line or adjunctive rather than primary default therapy in otherwise healthy dogs.

In contemporary practice, it is more commonly used as an add-on when phenobarbital alone does not achieve adequate control.

Levetiracetam

Levetiracetam has an appealing safety profile and minimal hepatic metabolism, which makes it attractive in certain cases. However:

- Its short half-life requires more frequent dosing (unless using extended-release formulations).

- Long-term durability data as sole first-line monotherapy are less robust compared to phenobarbital.

- Some dogs exhibit “honeymoon effect” response followed by breakthrough seizures.

Levetiracetam is often an excellent adjunct therapy and may be preferred in dogs with hepatic disease, but it is not universally considered the default first-line monotherapy in otherwise healthy dogs.

Prescription Diet

A prescription diet is a valuable supportive tool, but it is not typically considered a standalone first-line treatment for idiopathic epilepsy.

The best-known dietary intervention with evidence in epilepsy is a medium-chain triglyceride (MCT)–enriched diet, which has demonstrated reductions in seizure frequency in some dogs when used as an adjunct. Importantly, dietary therapy is generally positioned as add-on support, not a replacement for antiseizure medication in dogs meeting criteria for treatment.

Where prescription diets can add meaningful value:

- Dogs with partial control on medication

- Owners motivated for multimodal management

- Dogs where medication escalation is limited by adverse effects

- Cases where improving seizure threshold is a desired adjunct strategy

In short: diet can improve outcomes, but for most dogs with confirmed idiopathic epilepsy requiring treatment, ASM initiation remains the cornerstone, with diet layered in thoughtfully.

Clinical Framework for Starting Therapy

In practice, my approach follows these principles:

- Confirm diagnosis consistent with Tier I or higher confidence for idiopathic epilepsy.

- Discuss realistic goals with owners (reduction, not elimination, of seizures).

- Initiate phenobarbital at evidence-supported dosing.

- Schedule serum concentration assessment at steady state.

- Monitor liver enzymes longitudinally.

- Escalate or add adjunctive therapy based on response.

The goal is not simply seizure reduction, but long-term neurologic stability with acceptable adverse-effect burden.

Outcome-Focused Takeaway

From a specialty and systems-level perspective, phenobarbital monotherapy remains the most common and evidence-supported starting treatment for idiopathic epilepsy in dogs.

It provides:

- Predictable efficacy

- Objective monitoring capability

- Strong consensus endorsement

- Decades of longitudinal data

Newer agents are valuable and often essential as adjuncts—but phenobarbital remains the foundation upon which most successful long-term seizure management plans are built.

References

Bhatti, Sofie F. M., et al. “International Veterinary Epilepsy Task Force Consensus Proposal: Medical Treatment of Canine Epilepsy in Europe.” BMC Veterinary Research, vol. 11, 2015, p. 176.

Podell, Michael, et al. “2015 ACVIM Small Animal Consensus Statement on Seizure Management in Dogs.” Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, vol. 30, no. 2, 2016, pp. 477–490.

Charalambous, Marios, et al. “Antiepileptic Drugs’ Tolerability and Safety—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Adverse Effects in Dogs.” BMC Veterinary Research, vol. 12, 2016, p. 79.

Muñana, Karen R. “Management of Refractory Epilepsy.” Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice, vol. 43, no. 6, 2013, pp. 1161–1187.

Subscribe today and become part of the Clinical Outcomes Network.

Check Out Past Results

See how veterinarians nationwide answered previous Clinical Outcomes questions and what their results reveal.

Clinical Outcomes Annual Report

This report brings together the answers to more than fifteen of this year’s most important clinical questions, offering a comprehensive view of what is working in practices across the country.

2 Comments. Leave new

Love the result/pie chart!

Excellent resource